Building power for excluded workers in Washington, DC

“We were clear that we wanted to start and build something. We just didn't know what to build.”

That’s Noemi, one of the founding worker-owners of the Dulce Hogar cleaning cooperative in Washington, DC. For over a dozen years, she had been scraping by as a house cleaner, dealing with the everyday indignities and injustices of precarious employment in an industry built from the ground up on exploitation. For Noemi and her co-workers in the industry, simple things like “needing time off, to go to the doctor or to run any personal errands” that people enjoying more secure employment might take for granted, meant—at best—missed pay, and at worst, the loss of work. Even basic solidarity with co-workers was a big risk: “the injustice of not being able to help our fellow cleaning workers, because if you help them, then you also are at risk of getting fired.”

Was there some way to refuse all this injustice, to build something that would treat workers with the dignity they deserved? Trying to answer that question led Noemi to become a founder of Dulce Hogar, a cooperative designed to restore dignity and control to her and her fellow worker-owners. The journey started in a church basement, at the century and half old Luther Place Memorial Church on 14th St. NW, a hotbed of ministry for social and economic justice since the 1970s. Noemi—along with a few of her sisters, also working in the cleaning industry—were regulars at the church’s “Community Craft Collective,” a chance to come together to create handicrafts which could be sold at community markets. It was there, in the uncertain wake of the 2016 election, that they first met community organizers Kristen Kane and Bianca Vazquez. Bianca relates what these post-election conversations were like:

I have been around BCI— Beloved Community Incubator—since the very beginning. It started out really being an organizing story, a story about relating to folks. I was working at a church at the time, doing community work, when the 2016 elections happened—and I had a mentor who always told me, when in doubt, do a one-to-one. So that’s what we did. We started relating to folks—in church basements, in the hallways of their buildings, doing door knockings— just talking to people about what was going on for them, and the most pressing things in their lives. And after some of the immigration concerns, it was all about people's work. Work was the main stress. Work was what meant: could I pay rent? Could I not pay rent? Did I get to be with my kids? Did I not get to be with my kids?

This process of community inquiry, connecting with Noemi and her fellow cleaners, led to the launch of Dulce Hogar cooperative, built around the idea that a worker-owned cleaning company could give workers the support, flexibility, and dignity they needed to thrive in the industry. It wasn’t an easy road—for one thing, it’s hard starting a business when you are already grinding full time to survive. Noemi explains:

What was required was commitment as well as time to dedicate to building the cooperative, because building a cooperative is not easy, it's something that you really have to work towards. It requires a lot of patience, too. The work is flexible, but it is also a commitment to be an owner of a cooperative—you have to commit. We started with 8 people, and what happened was everyone wanted to work right away, so that they could pay their bills.

Working alongside these workers, Bianca and Kristen would help found Beloved Community Incubator (BCI), aiming to solve this puzzle where people were more than ready to own their own workplace, but lacked all the capacity needed to launch on their own. Noemi emphasizes the two-way street here: “what we learned is that we couldn't have done it as workers without the incubator. But if the incubator was there, and they didn't have us as workers, they couldn't have done it either. We really needed both of us to come together in order to make the project successful.”

Part of the support needed, it turned out, would be financial. Being a housecleaner is mostly about being a highly skilled worker, capable of doing a job as quickly as possible without compromising on care. But equipment—like professional-grade vacuums—does make a difference. When the co-op reached the point when they had more business than they could handle, and needed to onboard four new workers, that meant four additional vacuums. The money needed—around $10,000—was a modest amount in the grand scheme of things, but who was going to be able to finance this purchase? For most banks, let alone traditional investors, low-income women of color working as housecleaners wouldn’t even be considered for a loan.

The worker-owners of Dulce Hogar

To meet this need, BCI would decide to launch the DC Solidarity Economy Loan Fund (DC SELF), and joined Seed Commons so that they could provide the capital needed to the cooperatives BCI wanted to support—without having to take on all the overhead work of raising and managing investments themselves. For Bianca, because Seed Commons handles all the backend and admin work associated with investment and lending for members like BCI, it “frees up time for us to be on the ground with groups.” BCI staff can focus on the long and sometimes slow process of building trust and accompanying workers as they build cooperatives, providing low-cost legal services to this growing local ecosystem, while knowing that the larger cooperative will be there on the backend as they scale.

Seed Commons made it possible for that $10,000 loan for vacuum cleaners for Noemi’s four new co-workers to happen. The work of all eight people in the cooperative then made it possible for that loan to be paid back. As Dulce Hogar has grown, it’s become self-sufficient, no longer dependent on BCI’s ability to provide free backend business services. Noemi underscores this accomplishment: “what we're most proud of is that we can pay 100% of the cooperative’s fees and expenses, because we know that that means that the assistance that was provided by the incubator can now go to other people, and can help other cooperatives get on their feet as well.”

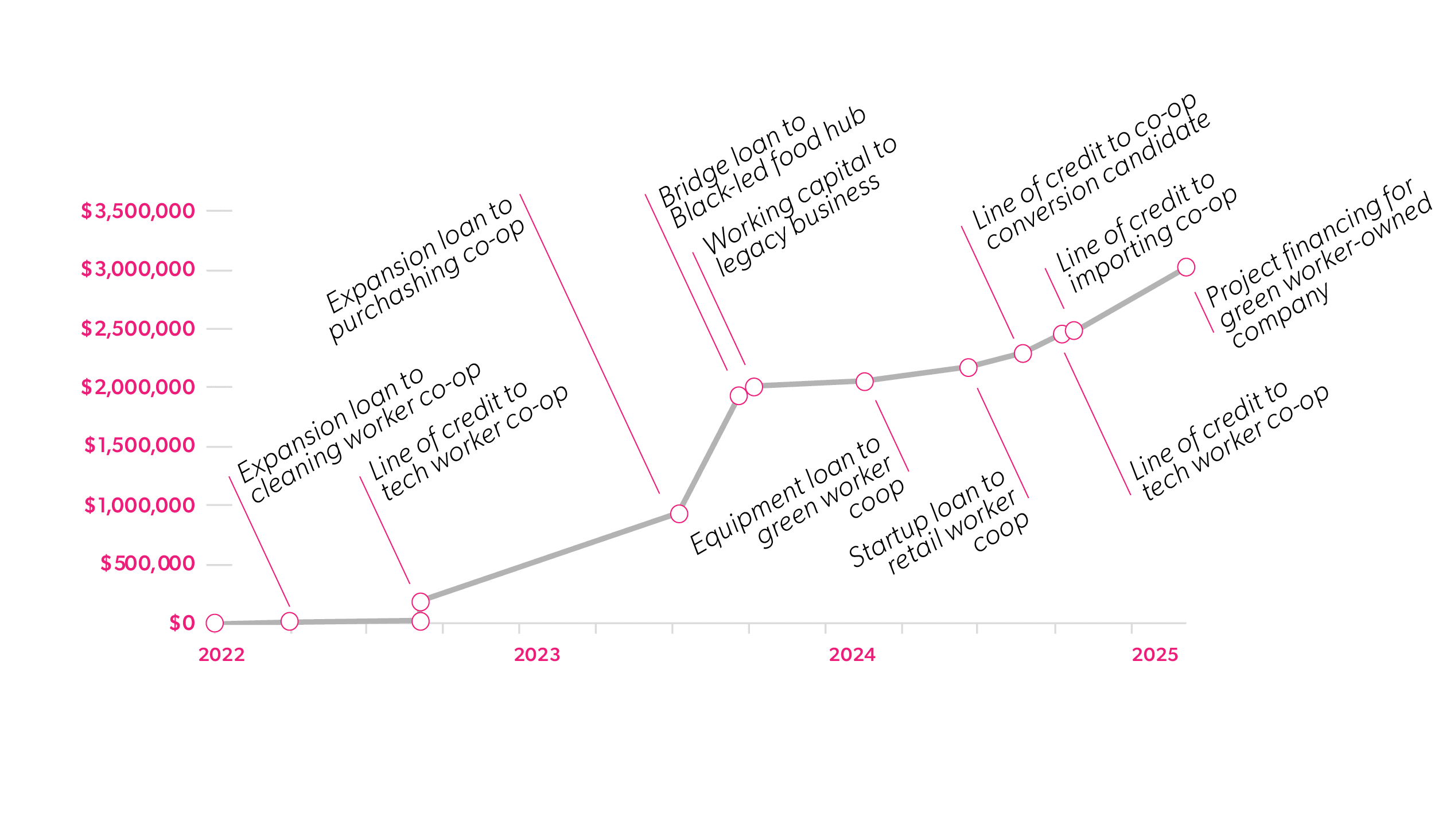

Noemi’s not exaggerating here about the impact of paying it forward as part of a cooperative ecosystem. Starting off with that initial $10,000 loan just over five years ago, BCI recently passed the $3 million mark in non-extractive capital deployed: there’s a lot of cooperatives getting on their feet in the DC region with BCI’s help.

Planting the seeds of a new economy

One of those cooperatives now on their feet thanks to BCI is the Swamp Rose Co-op, a landscaping firm focused on sustainability and native plants. Jeff Stottlemyer, a founding worker-owner there, describes himself as “a burned out climate finance guy who started tearing up my front yard”—going from banging his head against seemingly intractable and abstract global challenges to seeing the “disproportionate impact you could have on the local environment by just using your land a little bit differently, just by using native plants.” Working on a campaign with the local DSA chapter, he met the people that ended up becoming the other co-founders of Swamp Rose Cooperative, eager to connect their plant-nerd interest in ecological design with their interest in economic justice, and maybe create the democratic workplace of their dreams along the way. Jeff explains the motivation:

We had the hypothesis that the landscaping sector was particularly exploitative. The labor force is mostly made up of immigrants, many of whom are undocumented, but even for those who are documented, their jobs are rife with power imbalances, and wage theft, and just low wages in general. When the idea got serious, we started doing some more research, and we very quickly discovered, based on the data that we were able to find, that that was, in fact, the case. So it felt like, if we were going to address this major gap in the marketplace for ecologically-oriented landscaping services, we should do it in a way that also demonstrated a different, more democratic way of operating, showing that you could provide that kind of service, while also treating people much better, and treating each other much better.

Worker-owners of Swamp Rose, and their new truck

Starting off, the co-op was a weekend project, with the four founding members wading into an industry none of them had worked in professionally. It was a very DIY affair to begin with, with members using their personal tools and vehicles for their first season of work in 2022. One member—much to his spouse’s dismay—wound up keeping the co-op’s entire inventory of plants at their house. Swamp Rose’s worker-owners had connected with BCI early on for some legal advice around their bylaws and structure, but they were quickly realizing that without some resources to invest in the business and get to a real operating scale where they could go full time, they’d be running a real risk of burnout. With DC SELF up and running, backed by Seed Commons, BCI was able to extend a $50,000 equipment loan to the cooperative in 2024, giving them the ability to purchase a “beautiful” used commercial grade 2-ton pickup with a dump bed, alongside another smaller truck that a member had been lending to the co-op, and some key tools to make the work easier and more effective.

Operating now at real scale, the co-op has grown beyond its initial cohort of weekend warriors looking to get their hands dirtier than their nonprofit office and work-from-home jobs would allow, and now includes industry veterans on the worker-ownership team. They’ve scaled from four part-timers to six full-time worker owners, with three other team members in their trial period to become co-owners of the cooperative. And that cooperative structure is letting them build a different kind of landscaping company: for instance, they’re able to collaboratively plan for the offseason, lining up the backend tasks and “hardscaping” gigs that can keep the team working when it’s too early to be putting plants in the ground. To their surprise, Jeff notes that the co-op model has also given them a competitive edge in the marketplace:

We never really led with the co-op piece—we led with the plants, we led with making people feel comfortable that we were going to be able to provide what is a fairly expensive service. But we receive questions and comments and compliments about the co-op structure far more frequently than I expected. [...] There are now a couple other firms that can do this kind of work in the DC area. But none of those are cooperatives, and they aren’t working to address many of the more challenging labor issues that we see in the conventional landscaping trade. [...] It was actually very helpful for us to be a co-op for our marketplace positioning.

BCI’s support has helped them think bigger—they started with an idea of what an alternative could look like, but it was “kind of small ball.”Jeff notes that BCI’s “savvy” and “the scope of their vision” has in turn inspired them to “think with that level of ambition” too, knowing that BCI can be there for them to “help put the pieces in place to take the steps toward that vision.” Part of that might involve building on the foundation of trust between the cooperative and the loan fund to unlock a higher level of scale—Jeff notes that they are “increasingly playing in larger, more sophisticated project worlds, where there will be a need for more complex machinery as well—bobcats, forklifts, things like that. There’s a next level of capex that we’re pretty close to, but not quite ready for yet.”

Scaling up the ecosystem of cooperation

When they get there, BCI will be ready. Building their loan fund, DC SELF, as a member of Seed Commons has made it possible for them to think much bigger, and for the communities and workers they collaborate with to dream bigger. As Bianca notes:

Without the loan fund, we would be really, really limited to developing co-ops that didn't have high start up costs—ones with no equipment needs, no brick and mortar presence. And that is pretty limited to the service industry. What we're hearing—what access to capital does—is it gives people way more freedom to think about: what are the kinds of businesses that we need in our community? What are the kinds of businesses that we would be excited to work at? And that's something that just wasn't really possible before.

In 2023, BCI significantly scaled up their lending activity, with their largest investment to date at that point, a $750,000 loan to the Community Purchasing Alliance, built around helping an already successful community institution take their work to the next level.

Amy Abbott, the organization’s co-executive director, is the first to admit that “our organization is hard to describe, and sometimes even well-meaning people don't get it quite right.” It’s a cooperative, made up of local community institutions as members, that pool their economic power to “shift spending to locally-owned, woman-owned, BIPOC-owned businesses, to really ask questions about worker equity, worker benefits, and to align their spend—their money power—with their own values.” It’s an intervention “upstream” from so many of the ground-level problems these institutions see everyday, one that zooms out to imagine what collective economic power can do to address root causes—but it’s also a way for those institutions to save significant amounts of money, pushing back together against bad contracts and price gouging.

CPA started organically in the wake of the 2008 financial crash, in conversations between a dozen congregations that were already connected through an interfaith network. Gathered together for a meeting on a totally different topic, the subject of electrical bills came up, and as Alex Smith, DC Deputy Director, tells it, “they started lamenting the fact that ‘we’re paying our electric utility more than we're paying our pastor, our rabbi, our minister.’” In a newly deregulated local energy market, they realized there might actually be an opportunity to do something about this, by going in together on a group purchase, something none of them had experience with, but which a year later turned out to have saved the group around a hundred thousand dollars. Alex notes that one of these congregations, a large synagogue, might have been able to get this kind of deal on their own, but their peers—much smaller, historically Black churches—would not have been able to. Sticking together in solidarity was critical.

The seed was planted. The electrical purchase turned into a RFP for photocopiers, another market where smaller consumers often face opaque pricing and extractive contracts. With collective purchase after collective purchase taking place, what had been an informal group of a dozen congregations snowballed into something like 50 institutions working together—not just houses of worship, but now housing co-ops, charter schools, and other nonprofits. As impressive as the impact was, none of the individual institutions had the capacity to manage this on a volunteer-basis, on the edges of all their other important work, so in 2014 they incorporated as a member-owned, not-for-profit purchasing cooperative. Today, CPA has 90 member owners, and another 200 participating organizations. And that’s just in the DC area—there are now sister cooperatives in Cleveland and Boston, with another 200-300 organizations participating. In DC alone, just in 2024, CPA orchestrated a total contract spend of over $35 million, with $15.7 million of that directed to local small businesses, and $12.7 million of that total flowing to local BIPOC-owned businesses.

Isolated, none of CPA’s member organizations have much real power to shape the economic system—but together, their combined scale allows them to start to imagine something different. A case in point is their food system work. DC charter schools get federal funds to support school lunches, but are responsible for figuring out how to provide those meals on their own. CPA’s hypothesis was that if more of the food being served was made locally in DC, it would taste better for DC students, and those kids would eat more, and better. Through CPA, one school switched to a local, family, immigrant-owned vendor—and reported that student participation in the lunch program went up 40%. Now, CPA works with over half of all DC charter schools, contracting for over 10 million meals annually, and catalyzing an enormous shift to food produced locally in DC.

Even though these collective purchases unlock lower rates and pricing for the member organizations, the vendors CPA work with love the setup as much as the buyers. These days, it’s tricky to get in front of decision makers as a local company—tracking down the minister or rabbi who can make the call about who picks up the trash or where the HVAC service comes from is a hard proposition. But CPA bundles those opportunities up at a scale where the volume of business and the ease of customer acquisition more than pays for the discounts enjoyed by its members. In fact, CPA itself—with its fifteen person staff—covers all its expenses from vendor rebates baked into the contracts it negotiates.

Once you wrap your head around it, CPA’s model—a win for community institutions and local, diverse businesses alike—makes so much sense, ethically and financially. But back in 2023, despite an already impressive track record, they were struggling trying to convince lenders to help them add the capacity needed to fully take advantage of all the opportunities they could see to expand. There were more institutions ready to be recruited and onboarded, more sectors in which new purchasing relationships and contracts could be established, more community benefit and more opportunities for local small businesses, all paying for itself—if they had the capacity to put the pieces together. Amy notes that “it has been difficult for us in the traditional lending space because most traditional lenders do not understand co-ops.” But BCI—which emerged out of some of the same faith-based organizing networks that gave rise to CPA, did: “the connection with Seed Commons and BCI was just such a relief, because first, they understand co-ops, they understood us. And second, the terms that they were offering were just so much better than any traditional lender we had seen.” But more than that, it was the promise of a relationship that would go beyond the loan transaction that made working with BCI so appealing:

I remember Bianca saying to me very directly in the beginning—when something’s wrong, we want to be the first phone call you make, not the last. It’s not about us collecting a debt, it’s about the partnership that we are going to have, and we want to be partners in your success. We will all be lifted up when we succeed together.

Organizing as a core commitment

Part of why BCI works so well is because they approach the problem of cooperative lending as organizers, not as technocratic experts. In fact, they’re still organizers—outside of DC SELF and the co-op incubation work, BCI also plays a key role supporting worker organizing. A recent campaign, for instance, helped street vendors win the right to engage in commerce without being criminalized. Bianca notes that while “sometimes people are like, ‘what does that have to do with the co-op work?’” that BCI on the contrary sees this organizing work as squarely advancing the “solidarity economy,” imagining economic democracy more expansively: “the street is the commons, and written into the law for the vending zones is the ability for it to be self-managed like a co-op.”

Geoff Gilbert, who started as the organization’s Board President in 2018 and now works as BCI’s Legal & Technical Assistance Director, explains that the larger frame that drives and orients their work is support for “excluded workers”:

How are we working with excluded workers? Because sometimes people have multiple levels of exclusion. Maybe it is their immigration status. But maybe it is also where they're currently working. And maybe they’re formerly incarcerated. Maybe they have other challenges. But a really common thing I see is the people we work with being like: I didn't want to get abused at work anymore. I didn't want to not be able to take care of my kids. I want to be able to participate in community.

That’s why their ability to invest in deep, relational support for the projects they work with is so important. Bianca expands:

If we don't do this work, who will come to DC SELF with the ability to be “loan ready”—to navigate that process mostly by themselves? It's mostly going to be white people. It's mostly going to be college educated people. It's mostly going to be folks with access to more resources. So what does it look like to get serious about incubating cooperatives? What does it look like to get serious about training developers that do their organizing work east of the river? [...] There's a lot of fancy people in DC in the co-op space, inside big national organizations, that don't ever pay attention to what's happening locally, and who don’t have any idea of how to work with folks facing significant barriers to participating in a cooperative economy. I’m thinking about folks like the workers at Dulce Hogar. I don't think anybody there has an eighth grade education. Some of them didn't have emails when BCI started working with them. They don’t have a google calendar you can just send an invite to.

That’s why the low cost or free legal support that they’ve been able to offer to aligned businesses, sometimes for years before a loan is on the table, is so important. That support helps those workers level up their game, building trust and relationships. This is steady and patient work, and it creates a pipeline for loan readiness that brings in workers and communities that would otherwise be excluded.

While BCI does work with cooperatives composed of workers with more relative economic privilege—like the original founding crew at Swamp Rose, or the tech worker co-op Throneless Tech, who has been able to use non-extractive lines of credit through DC SELF to take care of their workers despite the sometimes glacial pace of large contract payment schedules, the idea is that increasingly that support from BCI means becoming part of a DC-area network of cooperative businesses that builds solidarity across race and class lines—not just thriving in isolation. The BCI Network now represents over twenty cooperatives and solidarity economy projects across the region, and in multiple different industries. Kristen Kane, one of BCI’s original organizers who is now the Director of Network & Membership, is excited about how they are continuing to work through this tension, with strategies like cohorts of community entrepreneurs designed to keep this growing network maximally inclusive:

Something that's exciting for us with these cohorts is we're getting good clarity around how to best set boundaries and organize our own capacity. The network [of cooperatives] is the umbrella for our work—but the network is only for operational businesses. If that was the only thing we were doing, that means that people need to have the ability to start without us, or, at least not need a huge investment of capacity development from us to get to that place. As you can imagine, the network would then start to skew more and more white, more and more towards people and projects with class privilege of various kinds. But, on the other hand, full incubation takes massive amounts of capacity, and doesn’t scale. The cohorts give us a way to do deeper capacity building for more co-ops, more effectively. We really focus on bringing more co-ops more proactively into the network, making sure that we're really building with a strong base of immigrants and working-class workers of color.

For BCI, this work isn’t some abstract application of a business development playbook—it is instead a kind of deep and relational organizing. Kristen explains that:

The foundational work of building a co-op, or keeping an ecosystem together, is the skill of listening. So much of keeping a group together is organizing—talking to people, finding out what they need, inviting them to take action on it together, building the group in the process, and then listening again. That’s the ethos that permeates our work.

This kind of listening isn’t always easy, especially in a place like DC, where the lived reality of the District’s longtime Black residents is often at odds with the upward mobility of those drawn to the capital for work in and alongside the government, and in the nonprofit sector. Bianca shares one difficult conversation she had as a transplant to the city, working in social service with kids who had never once been downtown to the Capitol:

I got told about myself so thoroughly in 2011 that it changed the course of my life. One of my neighbors, kind of agitated—and I’m not sure if she said “you people”, it might have been “y’all”—she said y'all come, and you play around for a year or two, and you get these fancy jobs. You don't register to vote here. You don't get involved here, and then you leave. And I was like, “Do I want to do that? What do I want my life to be about? Who do I want to be? Do I want to be contributing to that dynamic or not contributing to that dynamic?”

This is why BCI is intentional about the work of listening. In the summer of 2024, for instance, they conducted over 500 conversations across the region, talking with long-time residents, BIPOC business owners, and community leaders about the local economy, and what they were most worried about. Displacement was near the top of the list. DC’s housing market is punishingly unaffordable, for instance. Despite the presence of the landmark Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA), which in the past has helped convert many multifamily buildings into permanently affordable housing cooperatives, the current market, together with shrinking subsidies, has made it increasingly hard to secure these wins against displacement for tenants. So BCI is exploring how the agile, community-oriented capital they can bring to the table can help catalyze more cooperative conversions in the housing space, bringing other lenders on board quickly enough to take advantage of the short window of opportunity TOPA offers.

BCI also heard a lot of concerns about the displacement of businesses. With rents rising, many legacy Black-owned businesses in the District, essential to the fabric of their communities, have already been pushed out or pushed under. And with a generation of owners at many of these businesses poised to retire, there’s a real opportunity to think strategically about the connection between employee ownership and the geography of racial equity. BCI notes that many of the businesses in question tend to be on the smaller side—putting them off the radar of the ESOP conversion industry, which prefers to go after bigger targets. But BCI’s focus on community changes that equation.

One of the businesses they are helping explore a conversion to worker ownership is the venerable Sankofa Books, established nearly three decades ago on Georgia Avenue by filmmakers Shirikiana and Haile Gerima, and a vital local hub for people from across the African diaspora to connect around culture, history, and ideas. The Gerimas see a possible transition of the bookstore to worker ownership as a way to ensure that its mission is sustained for generations to come. As longtime employee Evan Wright, a member of the team exploring the cooperative transition, told the 51st: “Sankofa already stood as liberated territory, right? So there’s already this deep commitment to the mission and vision of the place. This was an opportunity to put a structure behind it that actually makes more sense.”

How BCI deployed over $3 million in non-extractive investment in under three years, starting with their first $10,000 loan in 2022.

All of these efforts to organize for a worker-owned economy get stronger because BCI is committed to knitting together the ecosystem behind the scenes. Working with CPA, for instance, they’ve been able to introduce Swamp Rose to the members of that purchasing cooperative, where the landscaping co-op has now become a preferred vendor. And BCI is able in turn to connect with CPA’s existing vendors— some of those local BIPOC-owned businesses might lack a real succession plan, for instance, and could benefit from support around a conversion to worker ownership.

In one particularly exciting transaction this November, BCI recently waded into the somewhat complicated world of DC-specific stormwater credits, where a unique regional market exists to incentivize the mitigation of water runoff with green infrastructure, like rain gardens and green roofs. But the small size and weirdness of this credit market makes traditional financing somewhat hard to secure—you have to build a green infrastructure project, first, to access the credits, which you can then sell off to pay the costs associated with building those projects out in the first place. BCI connected with Green Compass, a small employee-owned firm that works in this market, to provide over half a million dollars in project financing—but with the caveat that some of the work to install these projects, and to maintain them over the long haul as living infrastructure, had to be carried out by the Swamp Rose cooperative.

This is simply not the kind of the result you get with, say, an SBA loan from a mainstream bank. Those traditional financial entities are not going to be scheming about how the regional stormwater credit market could be leveraged to create more opportunities for the local worker co-op ecosystem, while shoring up the actual ecosystem with more native plants. But BCI will be.

And BCI will also be scheming to make sure that all of this is as inclusive as possible. One of the fundamental tensions about starting up worker cooperatives is that the workers most likely to benefit from them are least likely to have the financial privilege to spend huge amounts of unpaid time launching a new business—one reason, for instance, why many cooperative developers have started to focus on conversions over start ups. This is a real challenge, as Noemi from Dulce Hogar repeatedly underscored—there were many people who were incredibly excited about the possibility of becoming part of the cleaning cooperative, but, faced with the demands of keeping themselves and their families fed and housed, simply couldn’t make the commitment.

While there’s a lot that can be done around the edges to try to make sure that what BCI calls “excluded workers” get the chance they deserve to build democratic workplaces together, at the end of the day, people need to get paid to be able to focus on doing that, and it’s not always the case that it makes financial sense to finance the costs of that time out of anticipated future cooperative earnings. So BCI is breaking new ground, in a pilot project co-organized with Muslims for Just Futures, that combines co-op development with guaranteed income. Together, they’ve secured funding for forty people to receive $500/month for eighteen months while working on co-op incubation. That funding will be paired with increased support for BCI’s technical assistance efforts, so they can meet the demands of this large cohort of new cooperative entrepreneurs.

Getting the word out

As of this writing, the most recent loan made by BCI through DC SELF is a landmark for the Seed Commons network—it’s the first time its members have invested in a worker-led media organization.

The story begins back in 2017, when billionaire Joe Ricketts, who had snapped up the Gothamist network of city-focused online journalism outlets that included Washington’s DCist a few months earlier, abruptly shut the whole thing down a week after the editorial staff voted to unionize with the Writers Guild of America. The next year, with the help of two anonymous donors, a deal was struck allowing the sites to be relaunched with the help of local public media stations. DC’s WAMU, for instance, brought DCist back to life, to much acclaim. But in 2024, DCist died for good, with the station laying off digital staff and shifting away from online print journalism.

Maddie Poore had worked for DCist at WAMU on digital fundraising and member engagement, but left a few years before, realizing she was too frustrated with the slow-moving institutional culture of WAMU and its parent organization, American University. When the final curtain came down on the site, she remembers being at “a night of mourning”:

People had gotten together in a happy hour scenario, past, present, and recently fired employees of WAMU and DCist. I started going up to my friends there, and was like: what if we had a worker-owned newsroom? And some people were interested enough to hop on a Zoom, and we started meeting over Zoom and scheming. [...] There were, I think, a group of six or seven of us who said, for two months, we can dedicate ten hours a week to this thing. And we did that. It stretched on a little bit longer than that, but by July, we had launched our crowdfunding campaign.It was one of the most successful campaigns, money-wise, for a news outlet.

The 51st would emerge as a successor project to DCist, but rather than being controlled by a billionaire or a top-heavy institution, it would be accountable only to its readers and its workers. While not a traditional worker cooperative—they decided to incorporate as a 501(c)(3) to make sure that they were eligible for nonprofit support—the 51st is“a worker self-directed nonprofit,” and workplace democracy is built into the fabric of their structure.

BCI—which is, as a 501(c)(3), is organized in a very similar fashion, was happy to help. By 2024, BCI’s support for cooperative development was well known enough that Maddie and her once and future co-workers knew exactly where to go for help:

BCI were really, really helpful in figuring out how to even start thinking about setting this up. None of us came from a cooperative background, so getting resources and guidance and our questions answered and our legal issues detangled was really, really helpful. BCI was just so generous with their knowledge.

The homepage of The 51st.

BCI has continued to support 51st—as a member of the cooperative network, they can take advantage of technical assistance each month. BCI’s helped the team draft their policy manual, and has been called in to help facilitate tricky conversations around equitable compensation. They also learned a lot about business in the process of working with BCI to apply for the loan through DC SELF:

…in the process of applying for a Seed Commons loan, I’ve met with BCI a handful of times, assessing if the process and opportunity would be right for us, and getting guidance just from a business standpoint. But also helping us understand what non-extractive lending is has been so helpful. It's kind of one of those things that, you learn about it, and you're like, hold on, it could be like this?

Much like the loan to CPA, the loan received by 51st will help them power their growth faster than they could through slow self-financing of expanded capacity. With BCI’s help, 51st will be able to proactively develop their capacity to generate revenue and engage their audience, with the result that more local journalism gets funded by the people who depend on it.

This is a very different approach to capital than a lot of what you see in the traditional news media, where capital sloshes in, makes something splashy, splashy things get abandoned, and newsrooms get hollowed out or wiped out. Maddie notes that there are “really heartbreaking examples of promising newsrooms—and then you learn that they burned through $20 million in 2 years.” The 51st has a very different way of approaching their finances:

I think we have been really, really intentional about building in a way that is sustainable, and making sure we are only delivering on and promising what we can actually guarantee. Because it is really grassroots, because it's being built by people who are working class and don't have access to tons and tons of money, we're spending money in really intentional ways, and being really frugal where we can be. We want to shepherd and steward these community resources that are being put towards something that the community finds value in, and making sure that that’s actually where the money's going.

This is an ethos shared across the wave of new worker-owned media outlets emerging in recent years—Defector emerging out of the wreckage of Deadspin, Hell Gate launching in NYC. Journalists these days know better than many just how corrosive—and unaccountable to workers and communities—extractive capital can be.

The non-extractive support The 51st has now received from BCI is allowing it to grow differently, in a way that puts journalism and worker control before investor profits, and which does it as part of a larger community of practice and cooperative solidarity. Maddie explains:

We now get to meet with the full BCI network twice a year. I was on one of these calls, and there were forty different area-wide co-ops on there, and then we’re in breakout rooms, and I’m talking to people who are doing totally different work than we’re doing, but there’s knowledge being shared and similar questions that we’re all asking. It's been really cool to start feeling like we’re part of this community, part of the solidarity economy.

Now, especially with a potential monthly column on the solidarity economy in the works at The 51st, Maddie is excited they get to play a role in helping tell the story of the economy BCI is helping to organize:

How do we do more to spread the word, because it feels like there’s so much important work happening? People are distressed and witnessing collapse, and then there are these beautiful sprouts coming up, alternative ways that aren't destroying people’s lives. How do we actually put more attention towards that?